Texas’ “sex definition” law has raised concerns among intersex residents and advocates who say the measure could affect their legal documents, medical decisions and gender identity recognition.

House Bill 229, approved by Texas lawmakers last summer, defines men and women based on reproductive organs at birth and applies those definitions to state records. Some intersex Texans say the law may create barriers when applying for identification documents if their gender identity differs from their original medical records.

Mo Cortez, co-founder of The Houston Intersex Society, said his concerns stem from his own experience as an intersex person. Cortez was born with both male and female reproductive organs and underwent surgery at age five to remove his male reproductive organs.

“I do remember feeling a pain in my groin area and lifting the white sheet and seeing a red ‘X,’” Cortez said, recalling the procedure.

Rep. Ellen Troxclair, R-Lakeway, who introduced HB 229, described the measure as establishing a “clear, consistent and biologically accurate” definition of a woman and said it aims to protect the rights and safety of women and girls. Troxclair declined further comment.

State data show that of about 390,000 babies born in Texas between 2020 and 2024, 58 were recorded as having a sex “unable to determine,” according to the Texas Department of State Health Services. National estimates indicate up to 1.7% of people are intersex.

Adeline Berry, an intersex researcher at the University of Huddersfield in the United Kingdom, said intersex people encompass more than 40 variations involving sex chromosomes, hormones or reproductive anatomy. Some variations appear at birth, while others emerge during puberty or later.

While debating HB 229, lawmakers adopted an amendment by Rep. Mary González, D-Clint, stating that intersex people are not considered a third sex and must receive accommodations under state and federal law. González declined to comment.

Juliette Thurber, a San Antonio resident born with Klinefelter syndrome, said the amendment does not clarify what accommodations would be provided. The condition results in an extra X chromosome and can affect fertility and hormone levels.

“I literally fall into a third gender, according to this law, a third gender that is not defined,” Thurber said.

Rep. Jessica González, D-Dallas, chair of the Texas House LGBTQ Caucus, said the amendment had positive intentions but argued the bill still harms intersex people.

Medical interventions remain a major concern for some advocates. Cortez said doctors characterized his intersex traits as a medical issue requiring treatment, and he later underwent a phalectomy and gonadectomy. He said he has experienced recurring urinary tract infections since the procedure.

In 2016, three former U.S. surgeons general criticized cosmetic genital surgeries on intersex infants, stating the procedures were based on untested assumptions and often caused harm. A study published in the Journal of Pediatric Urology that same year found that 35 of 37 families offered surgical intervention for their intersex children accepted it.

Some advocates warn that policies defining sex strictly as male or female could encourage parents to pursue surgeries so their children conform to legal categories.

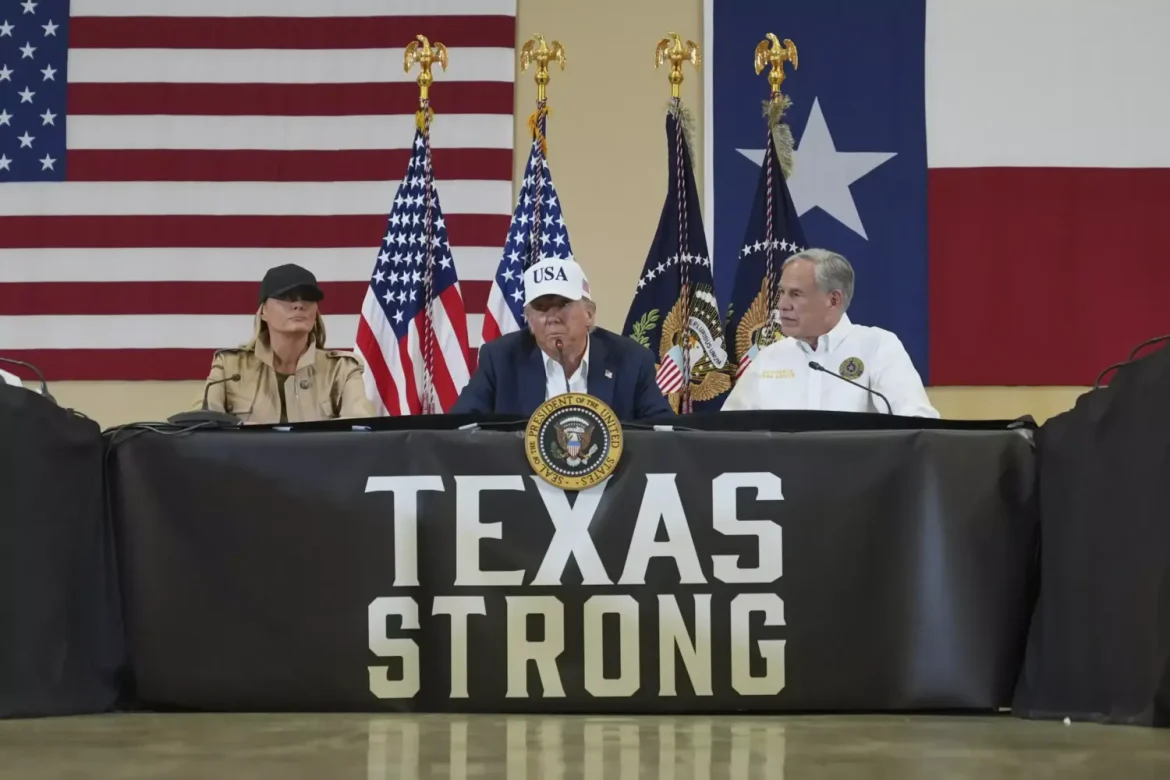

Government records present another area of concern. Before HB 229 took effect, some transgender and intersex Texans obtained court orders to change gender markers on birth certificates or driver’s licenses. Gov. Greg Abbott later directed courts not to recognize such orders, a position supported by Attorney General Ken Paxton in a legal opinion.

Shelly Skeen, a lawyer with Lambda Legal, said the law could result in mismatched documents if individuals previously updated their gender markers.

Troxclair and supporters have argued that most intersex people already have male or female listed on official records. Advocates say some individuals were not assigned a sex at birth or had both listed, creating uncertainty about how the law applies to them.

Sylvan Fraser Anthony, legal and policy director at InterACT, said the measure could create legal complications for those individuals.

Cortez said a Harris County judge denied his request in 2015 to change his birth certificate from female to male, but a Travis County judge later approved the change.

Thurber said her own request to change her name and gender in Bexar County was denied after Paxton issued his opinion, despite completing the application process and paying a filing fee.

Advocates say policy priorities for the intersex community include limiting non-consensual surgeries on children, establishing standards of care and expanding legal protections.

Fraser Anthony said bans on gender-affirming care for transgender minors often include exceptions permitting surgeries on intersex children, which they oppose.

Cortez said he wants children represented in decisions about intersex-related medical procedures and supports legislation that extends hate crime protections and safeguards for intersex individuals in state-run facilities.

Thurber said she hopes lawmakers adopt policies that recognize the complexity of intersex identities.

“Intersex people are going to get attacked in just the same way as trans people are,” Thurber said.